Hey family! As I polish up the last few pieces of the Underground Man and start to draft new material for the issue on The Outlaw (next series), I’m firing on both the illustrative and literary cylinders. One of the best pieces of creative advice was given to me by Joseph Young, someone I had the privilege of playing with and learning from back in my musical endeavors. I told him I really loved what yoga and breathwork did to my mind, but he was making such strides in his instrumental practice. He told me to take what I’d learned about yoga, meditation, and the breath and integrate it with my practice of art and music.

Of course at the time I thought I had everything figured out, and it’s only now that it’s become my idea that I’m paying any attention. Go figure. Why are we like that? In any case, seeds get planted, experience feeds their growth, and suddenly you are spending all your time in the overlap between recovery, creativity, and spirituality. So thank you Joe Young for trying to enlighten me.

Recently a close friend in recovery read some of the pieces on here and told me, “Yeah, that archetype stuff is all…” and he made the universal over-my-head gesture with his hand. That tells me that I’ve gotten the cart before the horse some and probably need to try a post that explains things more clearly—actually it probably shows gaps in my own understanding. So if I can ask a favor from you all, please send me any questions you’d like answers to, or clarity about as they relate to archetypes, archetypal images, recovery, creativity, and spirituality related to addiction treatment.

Readership is still growing, something like 80% of you are opening the posts on the same day they are published. Thanks a ton! And welcome to Part 7!

Sincerely,

Damon

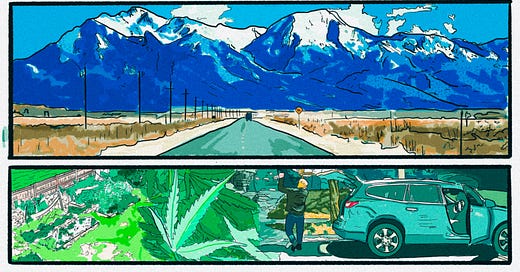

Cover Art: Scenes from the Summer of 2019-2020 (Illustrative Collage/Apple Pencil v1)

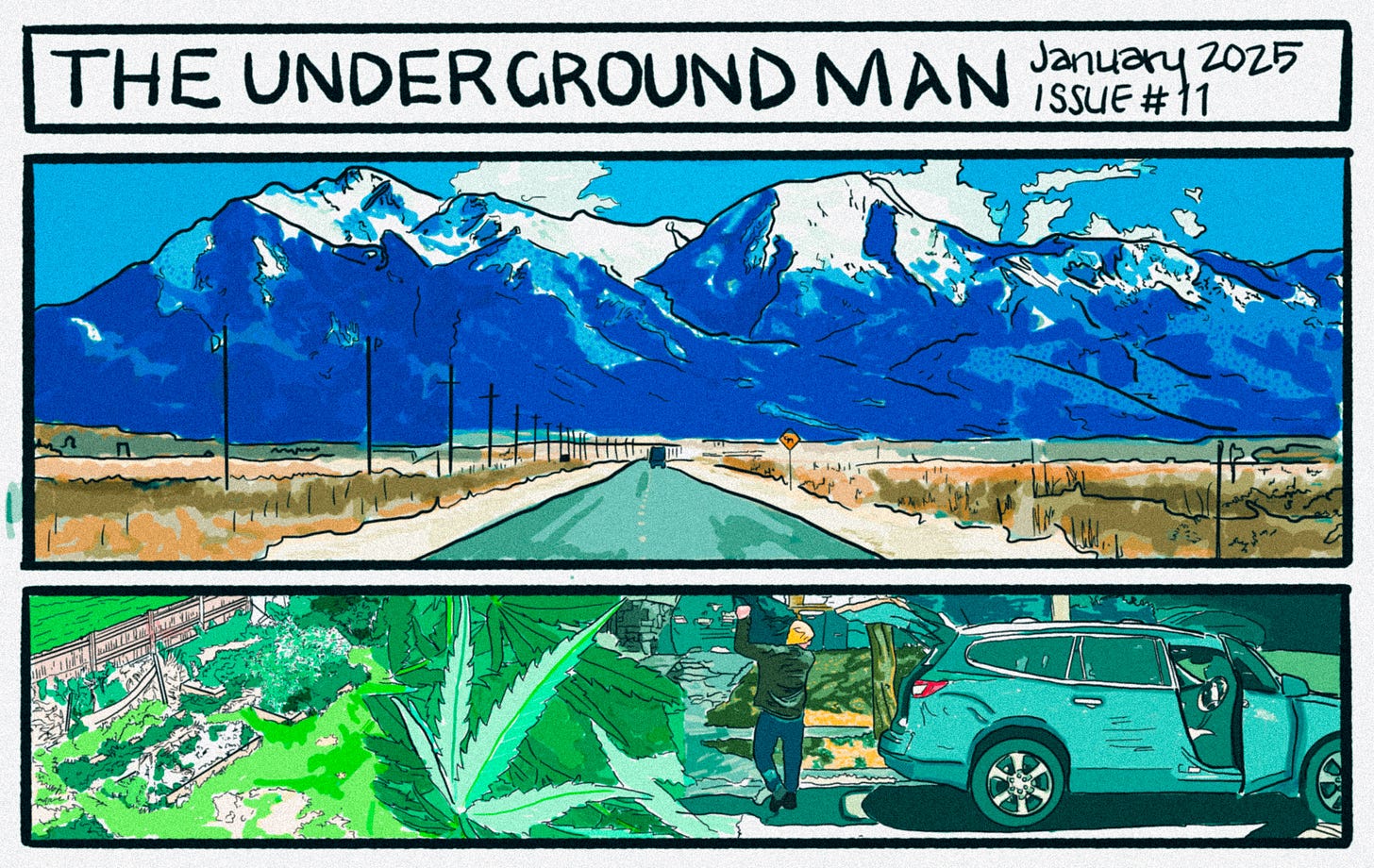

Top: Moonbeam’s Lot, Middle: Turkey Bags, Load Ready to Be Packed, Bottom: Self-Fulfilling Prophecy (Illustrative Collage/Apple Pencil v1)

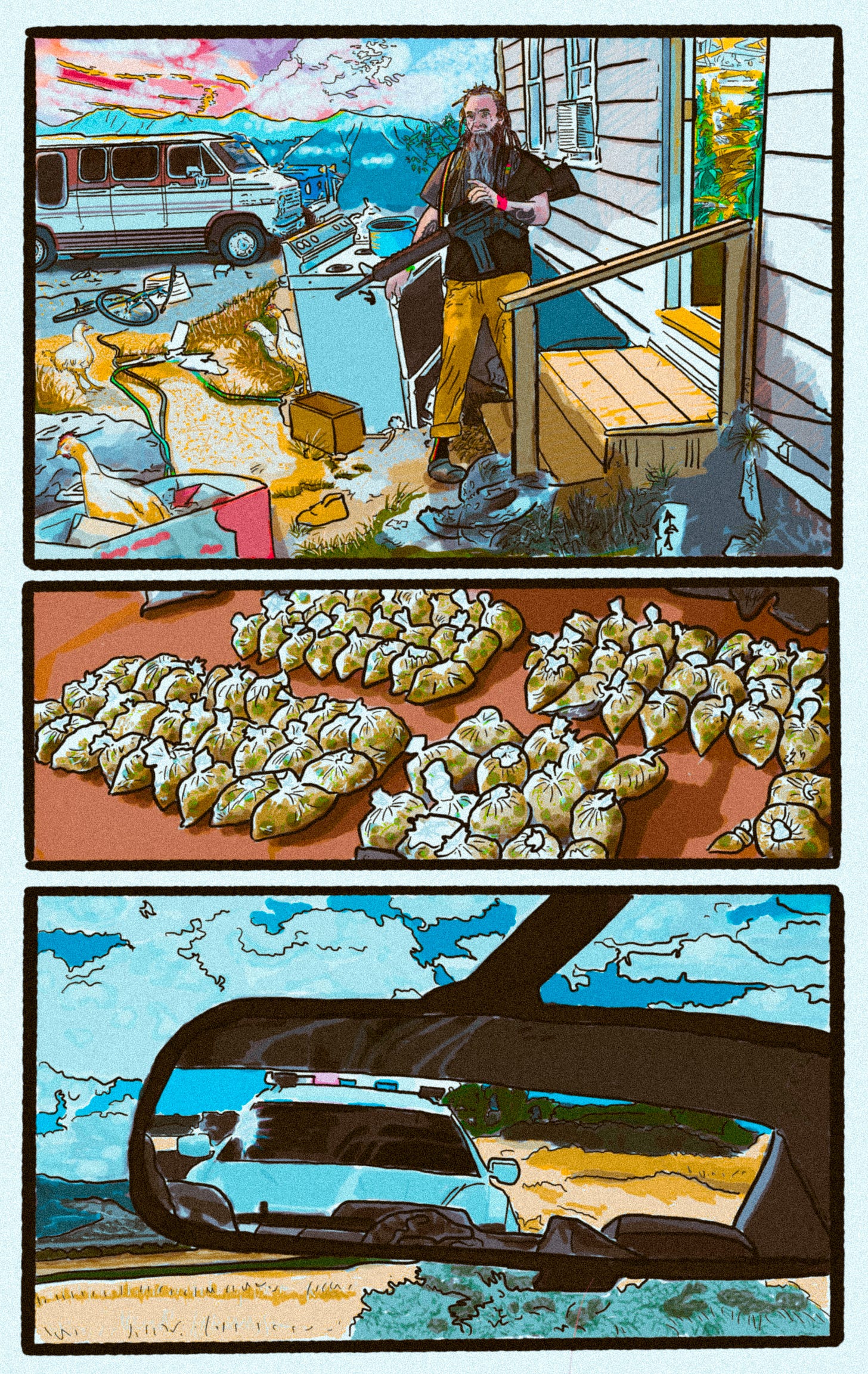

The Onset of Routine and Growing Addiction

In one move, I went from the Groundhog Day life of a corporate restaurant manager, kowtowing to the influencers, the foodies, the business assholes, and all stripes of suburban bourgeoisie, repeatedly humiliating myself for tips and reviews, complicit in the meaningless materialism and shameless self-deception, pouring booze on my self-loathing, able to see through the veneer of it all, but still craving to belong to it, feeling both better and worse, but never equal to anybody, I went from that—to pure fucking adventure. I was reborn.

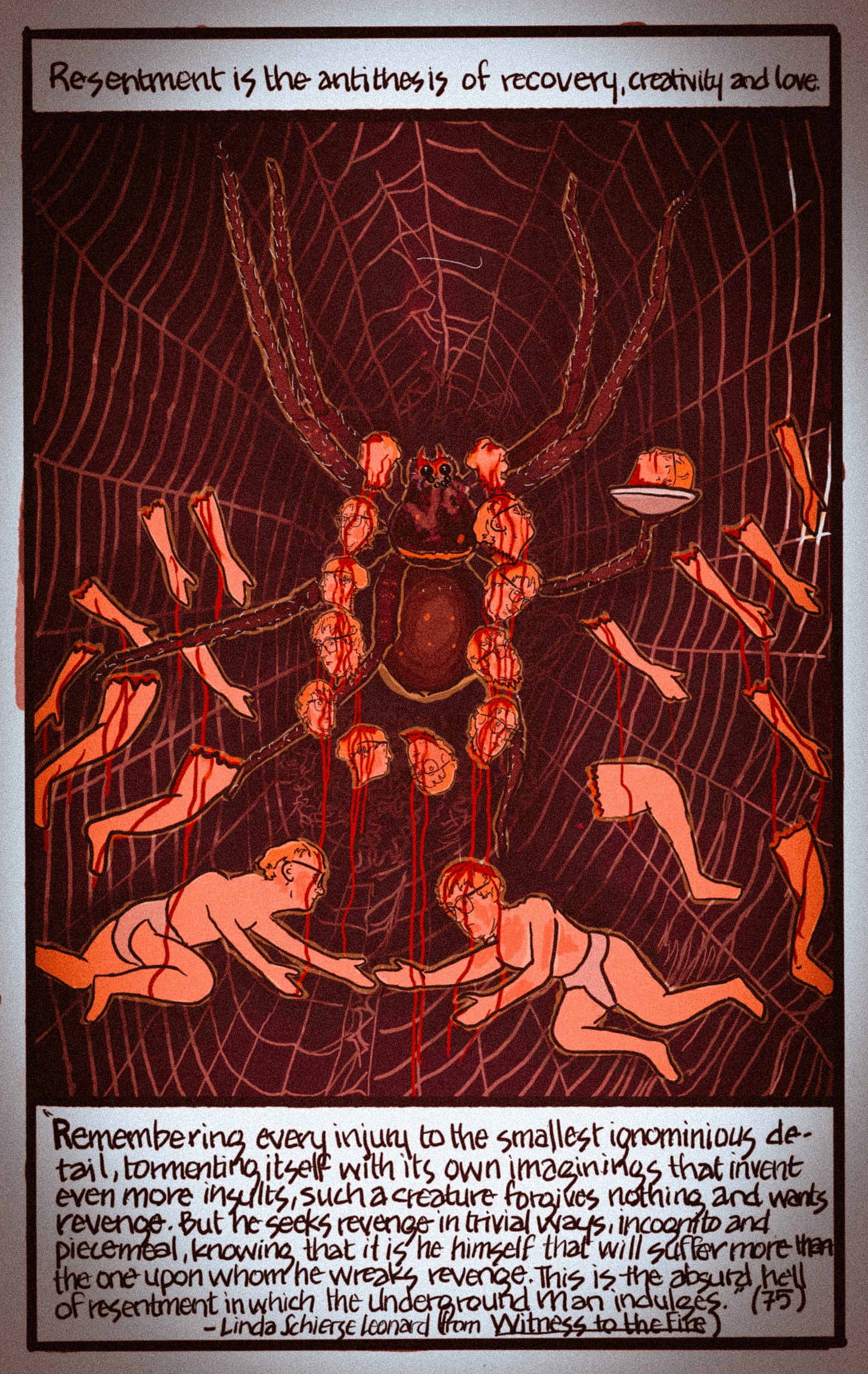

But even after reclaiming my independence, surrendering to the risks, meeting ate-up fuckers like moonbeam, being heralded for my triumphant returns, and the beautiful sight of money, stacking itself up to form little cities on my bed, even with a lifestyle change so drastic, routine took hold again. My solution once again became my problem. I judged, opined, and found things a little less satisfactory as the days went on. Brick by brick, mile by mile, I was unknowingly building my own prison again, increasing my need for relief. And then suddenly, I need a new life again.

I’d pull into the driveway at three in the morning, unload in the dark, and go inside to where my wife and kids were peacefully dreaming. I’d breathe in the smell of home—coffee grounds, dog hair, that indefinable scent of children, and self-obsessed, be unable to enjoy any of it. I’d promise myself, “I’ll make tomorrow all about them. I’ll take them to the park, go for frozen custard, or to some Disney movie.” I wanted to show them that they were my only priority. That all the risk was for them. But by noon, I’d be hiding in the basement, eyes glazed, counting money, carving out bumps of cocaine with the gummy edge of an old library card.

You tell yourself you’re still just dabbling, even when you start to organize your life around the next baggie. I became an alchemist of alibis. The basement became my command center, a damp, musty fortress of trash with weeds growing through the walls that held up the weight of my delusions. “I’m working on something,” I’d say when Natasha came to ask why I’d stopped coming upstairs. She’d grimace, look at me like she knew I was slipping into the dark water of my own insanity. “Fine,” I thought, “you’re a part of the problem too, bought into a phony reality, believing only in the joneses.” The sound of the children fighting would follow, muffled as if the distance between us was measured in years, not feet. “They’ll never respect me anyway.”

The first time I realized my routine was more than just a bad habit was when I ran out of kratom. It was supposed to be a backup, a crutch for the comedowns when cocaine left my bones feeling like hollow straws. I’d swallow those bitter, powdery doses religiously, shaking up the green sludge in an old water bottle and chugging it, trying to keep it from coming back up. I told people, “It restored my confidence, banished my anxiety, kept me awake or enabled me to sleep, whatever I needed at the time.” And then to myself, “yeah, to continue to produce, to perform, to keep my head down like a machine and serve, since apparently I was the only one who still valued authenticity.”

One day, I hit the bottom of the package and caught a moment of clarity, I’ve got to stop this. That was cute. A few days later, I was writhing in bed with the chemical cold sweats, tremors running through my legs, restlessly aching. My lungs felt like they were under a hydraulic press. I could barely get a breath. Anxiety sickened me, poisoned my every thought. I knew I was in deep and I was scared. Kratom wasn’t just some Kava Kava supplement they sold in headshops to hippie college kids. This stuff was actual junk and it had my soul. I’d been so willing, though.

From then on, the baseline changed. My mornings were built around making sure I had enough kratom to dull the edge and keep my heart from galloping out of my chest. I’d wake up drenched and dehydrated, stumbling to the kitchen where the powder-streaked counter waited like a silent reprimand. My hands, shaking with the precision of a junkie sculptor, would mix another dose.

God forbid I ran out on the road. The memory of those long, desperate phone calls to headshops in speed trap towns across the Midwest still makes me cringe. “Do you guys carry Club 13? No? What about Connoisseur Blend? No, listen, I don’t want the ‘White Bali’ crap. Yeah, I’ll hold.” Meanwhile, every minute without it had me seriously considering armed robbery.

But the interstate itself still called, and Moonbeam’s deliveries were getting bigger. One week it was 50 pounds, the next it was 80. I developed new routes, made more stops, got more daring with my pitches to newcomers looking to get involved. I’d tell myself the hustle was inevitable, that I better get used to it if I wanted anything close to retirement money, but the truth was, I was barely holding on. I couldn’t say no to anything.

Everything around me began to revolve around two extremes: the rush of each drive and the dread of withdrawal. Life at home became motionless, superficial, something that flickered in the background while my real existence played out in dark basements and the long, empty roads of nowhere.

By now, I wasn’t just a guy running weed to make a few bucks and get out of debt. I was the Underground Man in full bloom: isolated, cynical, convinced that the universe owed me a cosmic do-over. And all the while, the baseline kept shifting. A little more coke. A little more kratom. A little less of whatever it was that used to make life worth showing up for.

And so, the routine thickened, like sludge in the veins, each day a grayer shade.

Powerful